New Zealand-based photographer Jay Lichter possesses a unique talent for unveiling the extraordinary beauty hidden within the ordinary. Driven by a fascination with the natural world and a keen eye for the unusual in the seemingly ordinary, he has devoted himself to capturing the stunning beauty and intricate details of enigmatic organisms. All using his unique lens!

For the photographs, Jay focuses his search on rotting wood and investigates scraps of bright color, often finding hidden gems in the most unexpected places. His most recent focus is on the often-overlooked world of slime molds. He brings this universe to light through his stunning macro-photography; capturing the intriguing colors and textures of the slime molds, and presenting them through a macro lens.

A Casual Hobby That Turned Into a Photography Journey

Jay’s forays into the world of photography started as a casual hobby. For many — including Jay himself — mushrooms were previously perceived as nothing more than supermarket produce. However, his perception changed when he began to appreciate the great variety within the fungi world.

His fungi obsession soon expanded to include slime molds, which are often mistaken for fungi but are, actually, a separate group of organisms, since they often share habitats. Slime molds are, actually, single-celled organisms that can move and change shape. They are known for their lively colors and elaborate patterns. Despite their beauty, they are often overlooked due to their small size and elusive nature.

The New Zealand photographer, therefore, started his artistic photography journey using an iPhone with a broken screen to capture the elusive organisms. He soon upgraded to a macro-camera setup, which allowed him to immortalize the microscopic spectacles with incredible detail and clarity.

Jay Lichter's Photography of Slime Molds

The artist's passion for slime molds goes beyond their apparent aesthetic appeal. He is drawn to the intriguing behaviors of these organisms, which display a remarkable range of abilities despite their lack of brains. Jay finds their ability to communicate using chemical signals and navigate mazes, particularly fascinating.

This interest extends to the practical applications of slime mold research, including their potential use in solving complex optimization problems, such as improving traffic networks.

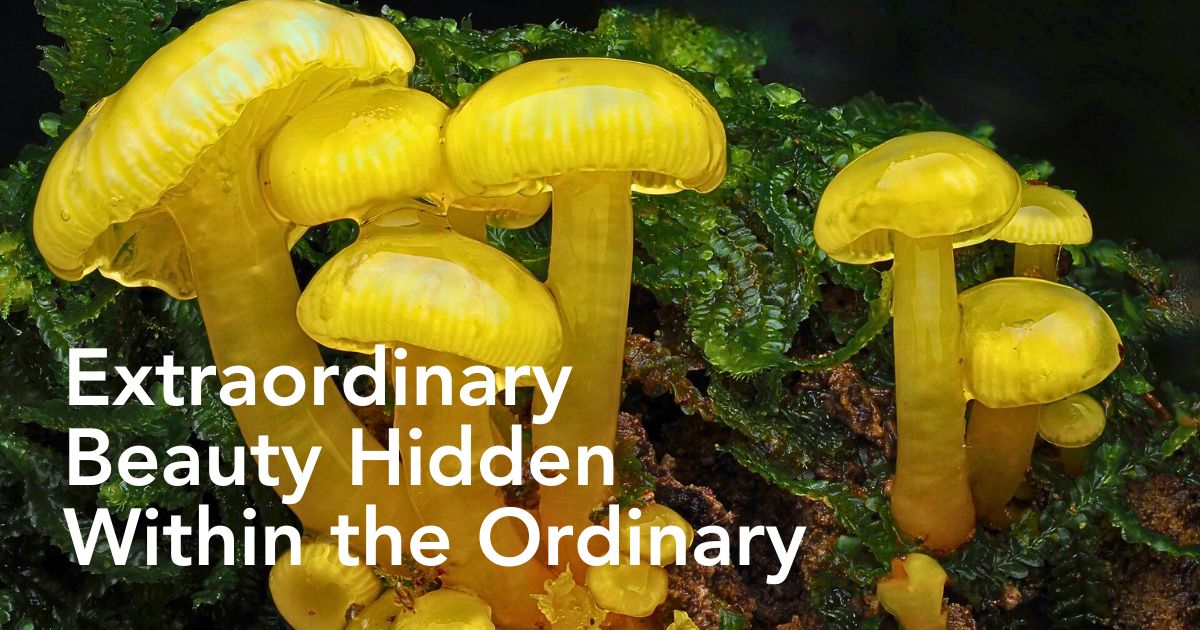

Currently, his artistic repertoire encompasses a diverse range of slime mold species, which are the focus of his most recent compilation. One of his most striking finds is the Mycena roseflava, a tiny pink specimen that resembles sugar-coated candy. Its impossibly small size, coupled with its distinctive color and texture, make it his favorite discovery. Another of his fascinating subjects is the Fuligo septica, commonly known as ‘dog vomit’ slime mold. This is a common species found in Mount Rainier National Park.

His favorite species, also, include the shiny, gloopy Gliophorus, which appears in a range of vibrant colors, and its entomopathogenic relatives such as Beauveria, Cordyceps, and Hirsutella. These organisms take over the bodies of insects that ingest them, creating a zombie fungus effect that has inspired popular culture.

Still, another of his rarest finds has been the endemic Mycena flavovirens, which grows only on rotting logs of Cyathea tree ferns. It's estimated that there may be fewer than 1,500 mature specimens of this green mushroom in existence at any given time. This makes it a really special discovery!

Jay often shoots photographs of these organisms in his own garden where they even grow on his houseplants. However, his favorite spots in Auckland have been the Hunua Falls and Gittos Domain in Blockhouse Bay. But the task is tiresome and requires a great deal of patience. On one shoot at Hunua Falls, for instance, he spent seven hours covering a one-kilometer path for just a dozen ideal discoveries for his photography.

The Fascinating World and Anatomy of Slime Molds

Slime molds, also known as Myxomycetes, are unrelated to fungi despite their long classification together. They are a diverse group of unrelated eukaryotic organisms spanning the Stramenopiles, Rhizaria, Discoba, Amoebozoa, and Holomycota clades. These organisms are a cosmic puzzle, exhibiting characteristics of both fungi and animals. They come in two main types: cellular and acellular (plasmodial).

The cellular slime molds spend most of their lives as individual cells. However, when they encounter a food source, they emit a chemical signal that attracts other cells to form a movable mass capable of amoeba-like movement. Each cell retains its individuality within this structure. When the time comes for reproduction, the cells aggregate to create a fruiting body, which releases spores that will each become a single amoeboid cell.

On the other hand, plasmodial slime molds start as individual amoeboid cells, but they merge to form a multi-nucleate mass enclosed by a single cellular membrane. These masses, also known as plasmodia, can grow to massive sizes. Some species have been recorded to cover over thirty square meters! Plasmodia mature into networks of interconnected filaments, moving as a single unit as their protoplasm streams along the network. These fascinating organisms are terrestrial, often found in damp, shady spots, such as on or within rotting wood.

The life cycle of slime molds is another intriguing aspect of their biology. This cycle includes a free-living single-celled stage and the formation of spores, which are produced in multicellular or multinucleate fruiting bodies. These fruiting bodies are formed through either aggregation or fusion, driven by chemical signals. Slime molds play a crucial role in nature by contributing to the decomposition of dead vegetation.

The small size and delicate nature of slime molds mean they have little to no fossil record. Moreover, their non-relatedness to other organisms means they are difficult to classify. They were long relegated to a catch-all kingdom, that of unrelated eukaryotic organisms called 'Protoctista'. This term is synonymous with the word 'protist', which is now used informally rather than in a taxonomic sense.

Recent estimates suggest there are around 1,000 species of slime molds, with the collection of environmental DNA suggesting numbers could be closer to 1,200-1,500. These organisms are diverse in appearance, with the largest and most familiar being the Myxogastria. Their size varies greatly, with some forming massive structures. For instance, the Fuligo septica species can cover several square meters, while the Brefeldia maxima can reach a massive 20 kilograms in mass.

The Myxogastria, or plasmodial slime molds, are the only macroscopically visible slime molds. They get their informal name because they are slimy to the touch during part of their life cycle. These organisms consist of a single, enormous cell with multiple nuclei enclosed within a single membrane without walls.

Meanwhile, the Dictyosteliida, or cellular slime molds, form swarms when their food source diminishes. The individual amoebae unite to create a multicellular slug, which then crawls to an illuminated spot and develops into a fruiting body. Some amoebae become spores, while others sacrifice themselves to become dead stalks, thereby aiding in spore dispersal.

That notwithstanding, the intriguing behaviors of slime molds have made many curious and inspired more research about them. These organisms exhibit complex behaviors despite having no brains. They communicate using chemical signals and respond to airborne chemicals. Additionally, they can learn and predict periodic unfavorable conditions, demonstrating an ability to adapt and think ahead. It doesn't end there. Slime molds also possess remarkable problem-solving abilities. Research has shown that they can solve mazes and find the most efficient paths between locations, making them invaluable in optimizing traffic routes.

That said, Jay’s photography has not only brought attention to the beauty of slime molds but has also generated interest in their role as ecosystem heroes, just as American mycologist Paul Stamets famously described fungi as the planet's grand recyclers, breaking down organic matter and returning nutrients to the soil. These photographs bring out the true beauty of these organisms.

Photos by Jay Lichter (@cyanesense).