Since I was on the road and in the air more and more, I suggested Maurice to change the post ritual. Rather than having the surface mail go round from desk to desk to end by Maurice’s pigeonholing the letters for follow-up and an increasing number of faxes waiting on top of the faxing machine to be read, why not have Maurice decide who would be responsible for the follow-up and photocopying for the others? Maurice eagerly agreed, with the photocopying carried out by the newly hired young secretary, Julia. A local 19-year-old, red cheeks, Julia always was in good spirits, except when Maurice would tick his spoon against his coffee cup, indicating he wanted another cup. Julia’s desk could just be squeezed in the small office.

Maurice and I, gradually adapting to our new roles, would meet with visitors in the round assembly room adorned with the company’s history in medals and cups. Somehow, we attracted more and more attention of the Dutch propagators. Theo Huygen of Van Steenwijk Plants, besides plant propagator also the Dutch agent of Groupe Ferry, came to ask for the Witte de Wit agency for India. Many rose growing projects were being started, subsidized by the World Bank, and Indians were hard-working, flower-loving and thus the potential huge. Of course, Theo then wanted his 50% royalty share. Maurice was excited with the possibility of some extra guilders coming in. I was skeptical. I had been gathering information on rose production worldwide and for sure India was not in the top ten. Since my sources had been limited to government reports and the occasional article in the ‘Vakblad voor de Bloemisterij’ (Dutch weekly floricultural magazine), I told Theo that we would discuss it and react to his proposal at short notice.

Likewise, father Ad Coen and son Eric visited. After discussing the Dutch market, on which Coen Roses had become less and less active for cost reasons, flower prices at the auctions and the VRV discussion on the introduction of variety labels, Eric unfolded his proposal. He had traveled extensively to Spain and Portugal, did his research and came to the conclusion that the future of European rose growing was in this Mediterranean region. Since Witte de Wit was only and poorly represented in Spain by senor Sidonia of Armada Plant, he suggested Coen to take over this position for both countries, to which East Africa was also added as a natural extension.

Spain and Portugal, not top-10 either, I recollected. And, by the way, they would also like to represent us in Kenya and other east African countries. Now that was a runner-up country, but we were already represented there by LAVAL.

Maurice was enthusiastic with the idea and seemed to like the regularly blushing Eric. Before any commitment from his side could be suggested, I reacted that the proposal was indeed very interesting. Witte de Wit had started taking inventory of the rose world and would definitely come back to Coen after a personal visit to the area. “Besides,” I continued, “we have learnt that you already represent Vorbeck in this area and I don’t know the position of our shareholders on this.” Apparently, the Coens had not expected us to know this. Eric blushed heavily and Ad took over, mentioning something about non-exclusivity and the arrangement not being finalized with Rosen Vorbeck.

Uncle Piet also spoke positively about the Coens, who were always present at VRV meetings. These VRV members all seemed to be world travelers, except for Witte de Wit, although Father Dré had been in many countries, known in the first place for scenery, but never in Asia, South America or Africa. This year would be his last trip to Finland.

I had not mentioned anything to the Coens about what Piet Staphorst of Terra Blanca had confided me by telephone a day earlier. He had just come back from a visit to California, had come across flowers of Terra Blanca’s Esther® and Witte de Wit’s Leonardo® that had been produced in California, probably by a grower of Dutch origin and Piet suspected either Lammers Rozen or Coen of having supplied the plants. He had never authorized any delivery of Esther®. I had quickly checked whether any such delivery of Leonardo® was known with us, the answer being negative. Piet and I would keep in touch and try to find out more.

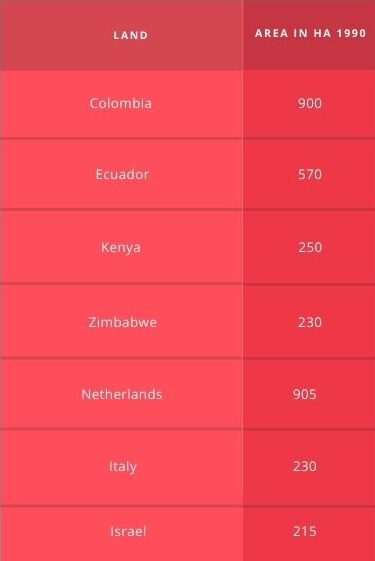

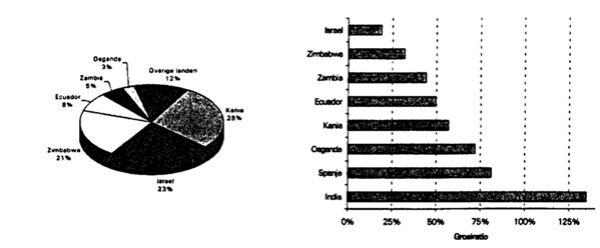

In my search for data I had regular contacts with fellow breeders, mainly Piet Staphorst, Hans Schulz, Bernd Solf, Arent Ruighaver, Agostino Crispi and Alain Ferry. I learned that they, like Witte de Wit, also had a network of agents, most being propagators. The breeders themselves had the same travelling pattern as father Dré, except for Alain Ferry and George Lebrun, who seemed to be established in Latin America, specifically Colombia and Mexico. The auctions had no information, or maybe they had, but were unwilling to share. They were cooperatives of Dutch growers and stayed away from imports. Then I was greatly helped by the following estimates, from a report of the Ministry of Agriculture (‘Businessplan Roos’, 1990):

“You see?”, Father Dré reacted when I showed him. “We have taken the right decision to focus on Holland and Italy through LAVAL. All the others are monkey countries.” That is also why he would have eagerly given the agencies to Huygen and Coen. “In those countries, there is no breeders’ rights legislation, so no obligation to pay royalties.” “Of course, we know that the propagators will try to cheat on us, but one guilder is better than no guilder and as long as Piet and the other breeders do their annual control in Limburg, the cheating is only on a small scale.” He had no awareness of Israeli or Moroccan propagators.

With various other breeders I had discussed checking on Israeli propagators in a fashion similar to the tradition of Uncle Piet’s controls in Limburg, where around 4 or 5 breeders or their agents would spend a few days walking around corn fields, armed with hiking maps to look for fields with rose bushes. They called this their annual ‘fishing expedition’.

“Wintergrafts and stentlings,” Uncle Piet had instructed me, “were intended for growers who grew on rockwool. The half-year-old bushes on Inermis from Limburg are a different story. These are for flower cultivation in soil, like the speedlings made by the VRV members themselves”. Later I had dug out my Elzas notes and drawings of the different plant types. It still was confusing. All the propagators had their bushes made by third party propagators in the south of Holland. The Inermis rootstock plants had been sown in Drenthe, the north east of the country, and dug out and transported to the south, where they were planted in fields. After some time, they were budded with eyes of the cutflower variety and after some six months dug out and stored in cool stores. This was the garden rose system. Occasionally, VRV members would take their clients to have a look at the plants. All propagators would show the same best-looking lots to their clients.

Control was difficult. Not only was it hard to recognize a greenhouse variety in the open air, but, even more complicated, there were hundreds of often small lots spread out over an area of between 50 to 100 hectares of woods, corn and wheat. The tradition had come for breeders and/or their Dutch agents to travel to Limburg together, split up in three groups of three persons, get hiking maps and walk the area for a few days, marking the lots, defining varieties, counting the plants and asking the locals for the ownerships of the lots. In the evenings they would come together in a small hotel to share their findings, but, more important, have a good time.

Sjef and Big Anton agreed to such a fishing trip to Israel. Staphorst, Ruighaver and I set the dates and would meet in Tel Aviv in the Dan Panorama hotel. Superplant and Witte de Wit shared the same agent: The Flower Bureau, the Israeli government organization for growers and propagators that also looked after breeders’ interests in the person of Micha Meir. It seemed odd, that one part of an organization would be checking on another part of the same organization.

Micha had made appointments to visit the premises of five propagators in two days. In the scorching heat, it turned out, and the prospect of violence omnipresent, even before I left Schiphol airport. I had to check in three (!) hours before departure, interrogated individually by different people on my background and the purpose of my trip. Up to that point I had always wondered why El Al was the safest airline.

At my first breakfast in the Dan Panorama I found out that the constant humming and flashes at night were in fact helicopters flying over sea and beach using their searchlights to look for terrorists. Despite this, the presence of military in all public places and the Uzis the people in the kibbutz would have at an arm’s length, I found the country extremely relaxed. One night, having dinner outside in Jaffa, police showed up with a robot at some 50 yards from our table to blow up an unattended package. The diners looked up with the explosion and continued to eat as if nothing had happened and this was a daily routine. Which it was.

The visits to the farms were also quite an experience. Much to Micha’s chagrin, one propagator, Beny Hazan Nurseries, had cancelled the visit. In temperatures of over 40oC without shade we walked these enormous dusty fields with endless lines of roseplants, looking for flowers and plant habits to determine the varieties in the absence of signs, then count the lines and pace the distance of a line and plants per step. The intense sunlight and blistering heat had faded the colors and shrunk the flower heads. If not for the extensive irrigation system, the plants would die within half an hour. The Israelis and the Dutch proved very similar in finding business and the one in keeping the water out and the other bringing it in.

Leonardo® was pink in Piet’s showcase and white here, with tiny flowers and leaves. We would take turns talking to the propagators, so the others could stroll around and investigate. Our collective expertise was truly surprising, and the propagator would eventually admit to our varieties and estimates, which Micha would then check with his reported lots.

Our fishing expedition was quite successful. Two of the propagators were caught with some counting mistakes of several thousands of plants each. They were warned and forgiven. A third, Giva’t Mohare, was roughly correct, but the fourth, Gideon Dayan Nurseries, had tens of thousands of plants of Audi®, Orleans® and Pacifica®, varieties of Von Bismarck and Rosen Vorbeck. Surprisingly, but probably not aware that we lacked this information, he confessed that he had not reported these. Micha did not represent these, so we decided to inform Bernd Solf and Hans Schulz and let them handle this themselves. Iko Chaim Litzman of Giva’t Mohare asked us if we would treat the Dutch propagators, mentioning the Haasse family, in a similar fashion. Of course, we absolutely did, but I made a mental note to discuss Haasse, a name I had not heard before, with Uncle Piet.

Micha afterwards told us that Beny Hazan had massive quantities of a variety called ‘Carola’, that he supposedly had developed in his own laboratory, but which in fact was Lebrun’s Mme Lebrun®. Of course, Lebrun had taken Hazan to court. The flowers were produced in Colombia, then flown to Miami, where Lebrun had taken action. Hazan only charged half the royalty to the Colombian growers, who, even if there would have been breeder’s rights legislation, did nothing illegal. After all, they paid the royalties. Lebrun should have sued Hazan in Israel, but was under the impression that the Israeli legal system was there to protect Israelis. The endlessly ongoing case cost Lebrun a fortune on lawyers’ fees. Luckily their fruit breeding brought in the necessary royalties to compensate.

We had ended up in the north of Israel and, although we only had one full day for the fishing, we squeezed some time in to visit Nazareth on the way back to Tel Aviv to see the big church that had been built on the place where Jesus was supposed to have lived and the chapel on the place of Jozef’s carpenter’s workshop. Surprisingly, there were not many tourists and the Palestinian souvenir peddlers mastered some typical Dutch: “Kijken, kijken, niet kopen.”

The next morning, we had to get up at 4 a.m. for endless waiting and interrogation at Ben Gurion airport. With the catch of the previous day, we decided to set up a meeting with Von Bismarck and Vorbeck in Hamburg to discuss our findings and try to establish a formal platform for our fishing activities. The seeds for IRBO were sown.

Two days later, a bomb exploded on the beach next to the Dan Panorama, killing a Canadian tourist.