Have you ever watched what would traditionally be considered a pot plant grow without a pot? Perhaps it even left you mesmerized. Well, that’s how kokedama works. These fascinating spherical garden sculptures, wrapped in soil and moss, and often suspended in midair, bring nature indoors with an intimacy that, perhaps, beats that of traditional pots.

Born from Japan's ancient gardening traditions and rooted in wabi-sabi, a philosophy that celebrates the beauty of imperfection, kokedama is a gentle way of reconnecting with nature. It shows sustainability and how the Japanese view plants, beauty, and the space between humans and the natural world. These green spheres speak of ancient tradition meeting modern living.

What Is Kokedama?

The word ‘kokedama’ breaks down simply. ‘Koke’ means moss, and ‘dama’ means ball. A kokedama is, therefore, a plant whose roots are cradled in a compact ball of soil, then wrapped entirely with living moss, and often suspended by a string or placed on a shallow dish.

It is different from traditional potting in that there is no ceramic, plastic, or glazed container between you and the plant. Instead, moss is the home, the support system, and the aesthetic all in one.

In contemporary gardening, gardeners often hide plant roots under the soil and conceal them behind pots. But Japanese gardeners looked at exposed roots covered with moss and saw their true beauty: the impermanence and the passage of time made visible. So, they sought to make an art form out of it.

Roots in Bonsai Tradition

Kokedama emerged during Japan's Edo period, although its exact origins remain pleasantly mysterious. Scholars, however, trace it to two specific bonsai traditions refined over centuries. The first is called ‘nearai,’ which means ‘no pot.’ In this practice, bonsai trees were removed from their containers, allowing their roots to hang free, sometimes anchored to pieces of driftwood or stone. Over time, moss would naturally grow on these exposed roots, creating something that looked almost forest-like.

The second influence is all about the resourcefulness of gardeners who couldn't afford ceramic containers. Thus, it points to ‘kusamono', which focuses on growing accent plants, often grasses and small herbs, alongside bonsai. These two traditions merged and evolved into the kokedama known today.

Kokedama was, for this second influence, often called the ‘poor man's bonsai'. Not as an insult, but acknowledging that it required far less maintenance, less specialized knowledge, and fewer resources than traditional bonsai. Anyone could create one at home without expensive pots, training, or a greenhouse. This meant kokedama appeals to people everywhere.

That, notwithstanding, kokedama developed alongside the Japanese understanding that plants exist in conversation with their environment. Unlike other gardening approaches, which often emphasize control over nature, Japanese plant traditions embrace cooperation. The moss ball is, then, a confluence of human creativity and the plants’ needs.

The kokedama practice nearly faded into obscurity during Japan's fast modernization, but experienced a renaissance in the 1990s. Across the world, kokedama artists today honor traditional methods while adapting them for contemporary spaces.

Incorporating Japanese Philosophy of Wabi-Sabi and Others

Kokedama embodies several Japanese aesthetic principles without stating them. For starters, one needs to know about wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic principle that runs through the entire practice. Wabi-sabi teaches that beauty lives in imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness. It is the opposite of the ideal of flawless, symmetrical beauty, celebrating asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, and the passage of time.

A kokedama personifies wabi-sabi wholly. The moss ball is never perfectly round. The plant is never precisely balanced. The moss might brown in places, showing its age. This realness is exactly the point, showing that you find beauty in this honesty, in the way nature grows without trying to be perfect.

Wabi-sabi is rooted in Buddhist teachings about impermanence in that, instead of being sad about transience, it teaches one to appreciate it. The browning moss, the slowly aging plant, and the gradual settling of soil all tell of time passing. Also, in Japanese culture, moss itself carries special meaning, symbolizing longevity and harmony with one's surroundings.

Moss works with the humidity and light it's given, content to stay in one place and become part of whatever surface it covers. For many Japanese plant lovers, wrapping a plant in moss (making kokedamas) means choosing to let it grow slowly, naturally, and in its own way, and allowing it to irregularly cover the ball as it changes its shape and ages. What starts as a perfect sphere gradually shifts as the plant grows and the moss thickens unevenly.

There is also ma, the concept of negative space. It comes into play when one suspends kokedama, making the air around it part of the composition. The string or wire suspending it may be functional, but it also defines the relationship between the plant and its surroundings. And there's also kanso, or simplicity. A kokedama reduces gardening to essentials: plant, soil, moss, and string. Nothing extra. Yet this simplicity creates room for attention. You notice a leaf’s shape more when there is no decorative pot competing for your eyes’ attention.

The practice mirrors Japanese attitudes toward nature. Instead of separating ‘wild’ from ‘cultivated,’ kokedama puts all these together. The moss came from a forest. The plant might have too. Human hands shaped their union. But the result feels discovered more than constructed.

What It Reveals About Japanese Plant Culture

Kokedama is not just a quirky gardening technique, but a window into how Japanese culture relates to plants and nature differently than many other approaches do. Japanese cities in the past centuries were crowded, and people missed the forest and the natural world. Instead of accepting this separation, they invented kokedama to bring it home with them.

This speaks to a different relationship with plants than what is common nowadays. Plants are not just decorative objects that should fit into spaces on people’s terms; instead, they are entities deserving of thoughtful care and space to grow while honoring their nature. A kokedama respects the plant's desire to have exposed roots and mimics how plants grow in forests.

The Japanese seem comfortable with plants being temporary and changing. A kokedama won't last forever. The moss will age, and the plant will eventually outgrow its moss ball home. And that's fine. This acceptance of change and impermanence gives kokedama gardeners a kind of peace.

Contemporary Applications and Sustainability

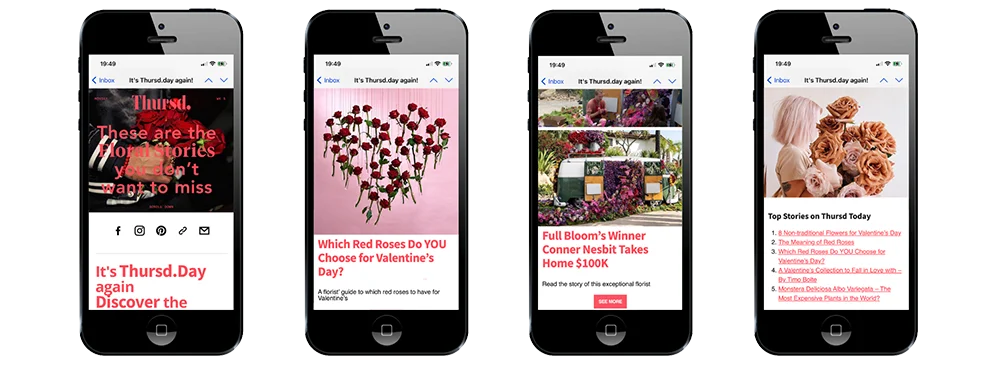

Nowadays, modern designers have taken kokedama in exciting directions. Floating gardens with several moss balls suspended at different heights create the illusion of hovering plants. Some create ‘kokedama paintings’ where strong plants are grown in moss balls and arranged on walls.

But one of kokedama's most appealing aspects is its environmental benefit. Traditional plant pots contribute to waste. A kokedama eliminates this problem. The moss is renewable, the soil can be remade, and the twine is biodegradable. When a kokedama reaches the end of its life, one can compost the whole thing without guilt.

Additionally, kokedama plants typically use less water than potted plants and don't require chemical fertilizers in high concentrations. The moss retains moisture effectively, reducing watering frequency. For people looking to live sustainably, it offers an ideal way to incorporate plants while treading lightly on the earth.

Creating and Caring for Your Kokedama

Making a kokedama is quite easy. First, mix two cups of regular potting mix with water until you have something that feels like thick, wet mud. The consistency matters because you need the soil to hold together but still drain properly.

Choose plants that prefer medium to bright indirect light and moderate humidity. Pothos, Philodendrons, ferns, ivy, and small-leaved plants work beautifully. Gently remove your plant from its pot and rinse away as much old soil as possible. Take your prepared soil ball and create a small hole in the center, nestling the plant's roots carefully without bending them.

Wrap moist sphagnum moss around the entire soil ball, layering until everything is covered. The moss needs to be damp when working with it. Use biodegradable twine or thin wire to wrap around the moss ball several times, securing everything together. Some skip the wire and let the moss hold everything on its own, but extra support makes the whole creation much more stable, especially if hanging.

Watering a kokedama uses the ‘submersion method. Fill a bucket with room-temperature water and completely submerge your moss ball for several minutes. Air bubbles will rise to the surface as water fills all the tiny spaces. When bubbles stop appearing, your plant has drunk its fill. In summer, most kokedamas need water once or twice a week. In winter, water every ten to fifteen days. Feel the weight of the ball. When noticeably light, it's time to water again.

Mist the moss every few days with a light water spray to maintain humidity. Light should be moderate to bright but never direct sunlight. Most plants suited to kokedama prefer understory conditions. A spot near an east or west-facing window works well. If moss starts turning brown, move it to a shadier spot or increase misting.

Fertilize the kokedama once a month during the growing season, typically April through September, by adding diluted liquid fertilizer to your submersion water. This gives the plant steady nutrition without overfeeding, keeping it healthy.

Notably, starting your first kokedama means accepting imperfection. Your initial attempts may look rough compared to professional examples. The sphere won't be perfectly round. The moss coverage might have gaps. But these ‘flaws’ often become its most endearing features, making it unmistakably yours. So, go ahead and try one.

Feature image by Gió Đông. Header image by La Florida studio.