Somewhere in a greenhouse in Oregon, a grower pauses over a Dahlia she's never seen before… A spontaneous cross-pollination, unplanned, unexpected. She could discard it. Market research says customers want predictable colors, uniform sizes, blooms that ship well, and last long. But something in this flower – a peculiar curve in its petals, an unusual depth to its burgundy center – stops her hand. She decides to grow it.

This moment, small and quiet, is an act of creative rebellion. And it's exactly what our world needs right now.

The Crisis We’re Not Talking About

While we discuss climate change and economic instability, another crisis unfolds beneath our awareness: we are losing our ability to create. Since 1990, creativity scores among children have consistently declined. We've become less emotionally expressive, less imaginative, and less willing to take creative risks. The very capacity that makes us human – the ability to imagine something that doesn't yet exist – is withering.

A recent read of mine – The Creative Act: A Way of Being, by producer Rick Rubin – describes creativity not as a talent possessed by the gifted few, but as a fundamental aspect of being human. "Creativity is not a rare ability," he writes. "It's our birthright." Yet somewhere between efficiency metrics and standardized processes, we've forgotten how to access what Rubin calls "Source”. That infinite wellspring of ideas flowing through all of us, constantly, if we're present enough to notice.

The floriculture industry mirrors this larger crisis. Trade shows showcase similar booths. Growers follow identical protocols. The market demands conformity, and creativity becomes a luxury we can't afford… or so we tell ourselves.

When Flowers Remember How to Create

But something is stirring. In farms across the globe, a quiet creative revolution is taking root.

The Slow Flowers movement, founded by Debra Prinzing, embodies what Rubin calls 'beginner's mind' – questioning industry assumptions about imported blooms and long-distance supply chains. These growers posed a simple yet radical question: What if we cultivated flowers for beauty, seasonality, and connection, rather than just efficiency and profit?

Farmers like Laura Beth Resnick of Maryland's Butterbee Farm practice what Rubin describes as 'patience and allowing.' She doesn't force roses to grow in the mid-Atlantic climate. Instead, she works with her region's natural rhythms, growing what wants to grow there, from snapdragons and tulips to buttercups that sell out before the bucket hits the counter. This isn't just regenerative farming. It's a creative surrender to what wants to emerge.

At Mini Falls Farm in New Mexico, Mykel Diaz and Lindsey Caviness grow specialty cut flowers based on the seasons – colorful Zinnias in summer and heirloom mums in fall. They're not trying to produce every variety year-round. They're listening to what the land wants to offer, when it wants to provide it. This is Rubin's creative philosophy in action: we can't force greatness, but we can 'invite it in and await it actively.'

What We're Really Growing

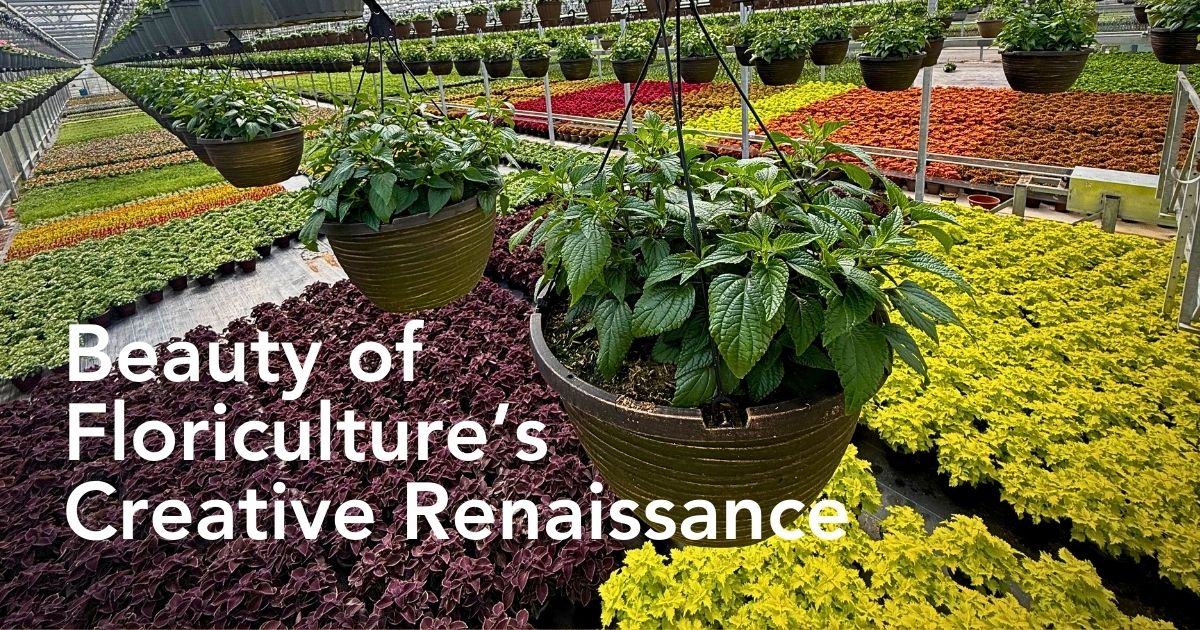

The beauty of floriculture's creative renaissance is this: these growers aren't just cultivating flowers. They're cultivating awareness.

Rubin describes awareness as 'actively allowed, a presence with and acceptance of what is happening in the eternal now.' That Oregon grower pausing over the unexpected Dahlia? She's practicing awareness. She's noticing what wants to emerge rather than imposing what should emerge.

When Hawaii's floriculture association named a new Anthurium variety after renowned designer Hitomi Gilliam, they celebrated years of collaboration between breeders, growers, and designers – what Rubin calls the four phases of creation: seed (the initial spark), experimentation (trying without knowing), craft (refining technique), and completion (knowing when to release it to the world). A new flower variety isn't just genetic innovation. It's a creative act years in the making.

The Stakes Are Higher Than We Think

When we lose creativity in floriculture, we lose more than beautiful flowers. We lose biodiversity as everyone chases the same profitable varieties. We lose the cultural meaning of flowers as they become commodified. We lose the human connection between grower and consumer. We lose solutions to climate challenges that demand creative adaptation.

But the stakes extend far beyond our industry. As Rubin emphasizes, creative solutions are desperately needed for the great challenges of our time. Climate change, social inequality, and global health. These require not just new technologies but entirely new ways of thinking. When floriculture reclaims creativity, we model what's possible for every industry suffocating under efficiency metrics and market pressures.

Rekindling What We've Always Had

What gives me hope is that creativity isn't something we need to invent. It's something we need to remember.

Every person in the floriculture supply chain – from the worker preparing soil to the florist arranging stems – can be creative. It's not reserved for 'designers.' The logistics coordinator who redesigns packaging sustainably is creating. The grower who notices a subtle pest pattern and tries an unconventional solution is creating. The florist who trusts their intuition over Instagram trends is creating.

When we rekindle creativity in floriculture, flowers become what they've always been: teachers. They show us how to break through soil, how to bloom in unexpected ways, how to trust natural timing rather than forcing artificial seasons. They remind us that beauty and commercial success can coexist, that efficiency and creativity aren't enemies.

Imagine if every greenhouse became a laboratory for creative awareness. Imagine if every stem carried not just color and fragrance, but the story of someone who dared to notice what wanted to emerge. Imagine if floriculture led the way in proving that industries can thrive by honoring creativity as essential, not optional.

The grower in Oregon still holds that unexpected Dahlia. She decides to propagate it. She doesn't know if it will sell. She doesn't know if it will become the next celebrated variety. But she knows something wants to be born through her hands, and she's brave enough – creative enough – to let it.

That's not just the future of floriculture. That's the future we all need.

Photos by Peter Ault.