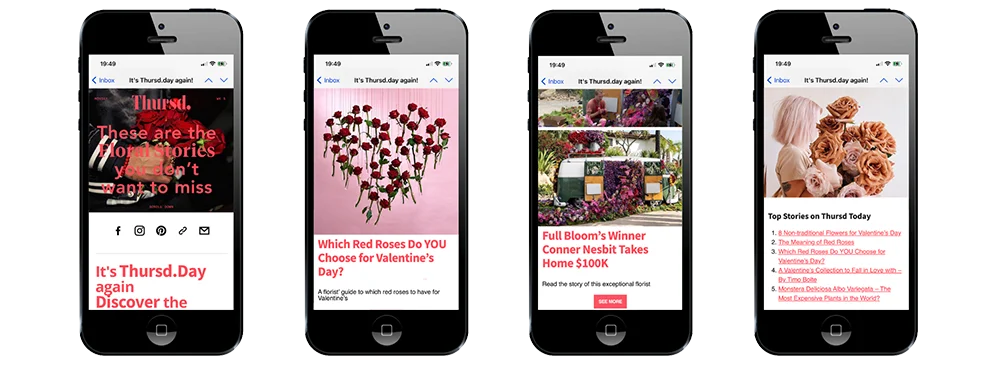

February 13. The day before Valentine’s Day, the same pattern returns like clockwork. Roses, tulips, mixed bouquets, and the entire floral supply chain suddenly become a headline problem to solve. Not because the world discovered a new reality overnight, but because a predictable media format loves a seasonal storyline that triggers emotion, certainty, and outrage.

Questioning the Framing

This is written on a personal title, not to deny challenges or pretend everything is perfect. But to question the framing. Because it is increasingly hard to ignore how often the world’s most human products, flowers, plants, and even fresh fruit and vegetables, are placed under a microscope, while supermarket shelves overflow with products that raise far bigger questions for public health, production ethics, and environmental impact.

The Annual Playbook That Rewards Negativity

Every major flower moment has become a reliable content format. Valentine’s Day. Mother’s Day. International Women’s Day. Easter. Graduation season. The press selects a theme, pesticides, carbon, labor, water, labels, and then amplifies it through radio shows, newspapers, and fast social clips.

This is happening in the Netherlands, the UK, the United States, France, and Germany. And other Western countries. Different accents, same script. The headline is often sharper than the research. The nuance rarely survives the edit. The emotional takeaway becomes the product.

The point is not that these topics should be ignored. The point is that the amplification is asymmetric. When something is found, it becomes framed as something dangerous. When improvements are made, they rarely become headlines.

Why the Sector’s Default Response Keeps Losing

When the sector is invited into these formats, the reflex is defensive. A spokesperson says the industry is improving. That innovation is happening. Those standards are rising. All true. But in a debate format built for negative stickiness, that response is strategically weak. It validates the premise and keeps the narrative centered on harm.

There is a better opener. A disruptive one that flips the frame without denying reality.

"Why are the most beautiful, human products so aggressively problematized, while supermarkets are filled with products that are objectively questionable for health, society, and the environment?"

That question does not dodge responsibility. It rebalances attention. It forces perspective. It reveals what is really happening. Flowers hit a sensitive nerve because they symbolize love, care, and meaning. They are emotionally loud. That makes them a perfect target for simple moral outrage.

Flowers Are Not Just Pretty, They Shift People

This part gets lost too often. Being around flowers is not just a lifestyle choice. Research has shown measurable physiological and psychological relaxation effects from exposure to flowers, including changes in brain activity and improvements in mood.

"Flowers and plants are good for you."

That matters. Because public debate often pretends flowers are optional, frivolous, decorative. They are not. They are a social technology. They help people mark milestones. They support recovery. They strengthen connections in a world that is increasingly digital and transactional.

Global Livelihoods Are Part of the Story

There is another silence in the seasonal outrage cycle. Millions of livelihoods depend on floriculture across the Global South. In countries such as Colombia, Kenya, and Ethiopia, floriculture is one of the most labor-intensive agricultural industries.

"Floriculture creates formal jobs, skills development, logistics infrastructure, and export pathways that did not exist before."

If the conversation is going to be ethical, it has to include what flowers make possible, not only what critics fear they represent.

Europe and the Netherlands as Innovation Leaders

The narrative also ignores how advanced European greenhouse horticulture has become, especially in the Netherlands. Biological pest control, integrated crop management, data-driven cultivation, water recycling systems, and precision climate control are not theoretical concepts. They are a daily practice.

"The floriculture sector is proactively driving sustainability, often moving ahead of regulatory requirements rather than simply responding to them."

Are there still residues found? Yes. Is the sector finished with its transition? No. But it is undeniable that Dutch and European growers are global frontrunners in technological innovation and in the shift toward biological alternatives instead of traditional chemistry.

Residues, Detection Limits, and Context

Yes, residues can be detected. That is not the debate. The debate is context, dose, and real exposure.

"Analytical chemistry today measures in parts per billion, trillion, and even beyond. When detection becomes extremely sensitive, found does not automatically mean dangerous. It often means measurement has improved."

Risk assessment bodies consistently distinguish between consumer exposure and occupational exposure. In realistic scenarios, consumers generally assess risk as low. Where the conversation becomes more legitimate is occupational exposure. Florists, auction staff, inspectors, and farm workers who handle large volumes deserve high standards, protective measures, and transparency.

That is where improvement should continue. Not through panic headlines, but through structural progress.

The Tulip Argument and the Bigger Point

There is often a rhetorical line thrown into debates about flowers, that someone would need to consume extreme quantities to experience health effects. Instead of exaggerating numbers, it is better to keep it simple. Tulips are not food. Exposure scenarios matter. Handling is not eating. Trace detection is not equal to a harmful dose.

The science of toxicology has always been built on one principle. The dose makes the poison. That context is often absent from the public conversation.

A Better Sector Response for Every Peak Flower Moment

Here is what I believe should become standard for anyone in our global sector who is asked to respond in the days leading up to Valentine’s Day or any other peak flower moment.

- Lead with the framing question. Why are flowers and fresh produce treated as guilty by default, while far worse products are normalized?

- Anchor on verified human benefits. Flowers contribute to emotional well-being and social connection.

- Put livelihoods on the front page. This industry supports hundreds of thousands of families globally.

- Separate consumer and occupational realities clearly and transparently.

- Bring nuance back into the conversation about residue. Detection is not automatically dangerous.

Valentine’s Day Should Be a Reset

Flowers are one of the few products that still carry pure human intention at scale. They are how people say "Thank you. I miss you. I am proud of you. I am sorry. I love you."

That is why they trigger scrutiny. That is also why we must stop reacting and start leading.

More transparency. Better occupational standards. Faster innovation. Clearer labeling. And a stronger narrative that refuses to let 'found' automatically mean 'harmful'.

This Valentine’s Day, instead of apologizing for bringing beauty into the world, let us ask better questions. Let us demand proportionality. And let us tell the full story.